The Horrors of Caregiver Burnout: ‘Pearl’, ‘Silent Hill II’, and What We Can Learn From Them

It's a hard job and not everyone is equipped to do it.

Caring for a loved one or finding yourself having to be cared for by loved ones is a challenge for all involved. Out of all the genres in which it’s been explored (romance, drama, comedy, etc.), the horror genre has managed to create some surprisingly nuanced and empathetic explorations of caregiver burnout and the horrors of having your life in someone else’s hands.

Pearl (2022) and Silent Hill II (2001) both not only break the mold but examine it.

Trigger warning: this article will cover ableism (especially violence against disabled people) and suicide.

Spoilers for Pearl (2022) and Silent Hill II (2001)

Pearl (2022)

What’s unique about Ti West’s newest film (a prequel to his movie X) is that while the story mostly follows the origin of its villain protagonist Pearl, the character whose perspective is most horrific is Pearl’s father.

Pearl’s unnamed father is completely physically disabled and therefore especially at risk during the Spanish Flu epidemic of the movie’s setting. Many scenes of him evoke the Grandpa from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1976), being wheeled around by the rest of the family and literally hand-fed. However, unlike the grandpa, Pearl’s father is still very mentally aware of his surroundings. His actor, Matthew Sunderland, is not disabled but manages to give a great performance with just his eyes. His terror is palpable as he is almost fed to crocodiles and has his life repeatedly threatened by the daughter and wife who care for him. He is essentially in a hostage situation with his own family, completely unable to escape or even scream, and his situation only gets worse as the movie goes on.

After watching his wife die in front of him, he is left sitting in the room she died in all night, unable to flee or go check on her body. When Pearl returns, it seems like she is open to continuing to care for him, cleaning him up and apologizing for leaving him all night. But he quickly realizes she only returned to finish the job.

Pearl’s dialogue makes it very clear that while she claims to be releasing him by killing him, she’s ultimately doing it for her own selfish pursuit of her goals, not wanting to be tied down by responsibilities. This interrogates the long history of killing off disabled characters with the justification that they are better off dead. Does anyone actually believe they are doing these characters a service, or is this just based on a long history of demonized disability and seeing disabled people as “a burden”?

That’s not to say it doesn’t have any sympathy for how hard care-taking is; Pearl’s mother, Ruth, is clearly trying her best to work their farm, take care of her disabled husband, and deal with a daughter whose carelessness and casual violence risks the lives of others. She is shown crying herself to sleep in a heart-wrenching scene and her issues appear to stem more from her daughter’s refusal to take responsibility than her husband’s condition.

Silent Hill II (2001)

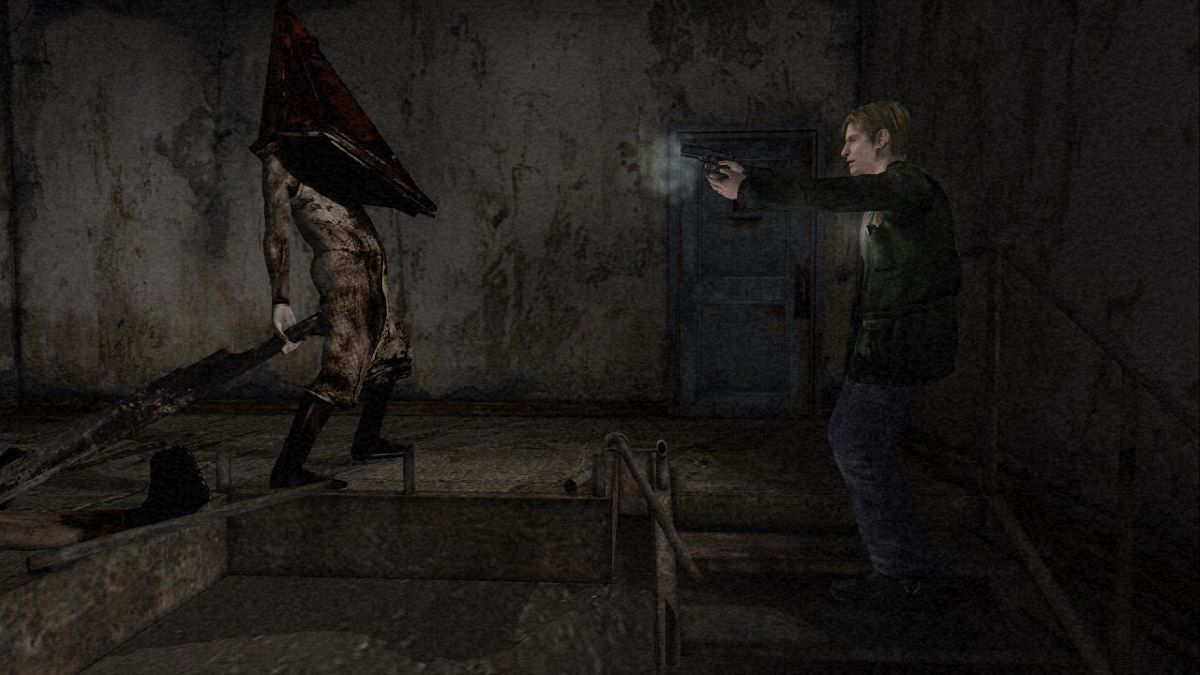

Another piece of horror media that comes to mind is Silent Hill II, AKA the game that created Pyramid Head. This story is still one of the heaviest ever produced in the franchise, following the widower James Sunderland as he confronts his own guilt over murdering his terminally ill wife.

What makes this game unique from the many other tired explorations of this trope are how the choices you make in-game affect the ending and how the multiple potential endings allow the player to choose James’ fate and decide how genuine his guilt is.

The “Maria” ending has James going off with his wife’s doppelganger, a seemingly happy ending ruined by her coughing and him warning her to see a doctor about it. James’ “reward” may be a shiny new wife, but it also means the cycle starts again, and James has seemingly learned very little.

The “Leave” ending is James at his most earnest. In it, James holds himself responsible for his actions and ‘confesses’ that he hated his sick wife and selfishly wanted her to die, but the apparition of her claims “If that were true, then why do you look so sad?” Grief is complicated; sometimes we hate the ones we lost because hate is easier to deal with than sorrow. Still, Mary forgives him in the end and asks him to go on with his life, releasing him of his guilt. There’s also an implication that he adopts Laura, a girl who Mary met in the hospital and considered adopting, showing how he’s building a new family but not forgetting his wife.

The “Rebirth” ending is relatively ambiguous and implies James may be looking for a way to bring Mary back, even if it’s an impossible task. Considering the supernatural aspects of Silent Hill, it’s hard to say whether this is a genuine goal or the ravings of a broken man. Either way, the future is uncertain for James Sunderland.

The “In Water” ending has James admit to his wrongdoings but he becomes so overwhelmed by the guilt of his actions that he cannot move on and thus drowns himself. This is made worse by the implication by the director and in later games that this is the canon ending and therefore the end of James Sunderland.

No matter the ending, we get the added punctuation of Mary’s last letter to him, apologizing to him and showing how she hopes he moves on with his life, which can be either a twist of the knife in the already guilt-ridden James or a demonstration of how Mary was always too good for James.

Ultimately, how sincere and how sympathetic James Sunderland is, is left up to player interpretation. This in and of itself shows how every caretaker and every cared-for person has a different experience with caregiver burnout and their perception of it.

What Horror Has to Say About Caregiver Burnout

There is still a lot of ableism in horror; the equating of mental illness with being violent or dangerous is baked into the formula of many ‘classic’ genres. Even the media I discussed in this article are not necessarily the gold standard.

But that doesn’t mean horror can’t also be used to interrogate those tropes, to highlight the truth behind their creation. What’s more, I think horror is especially good at showing us our own blind spots, our own weak points, and how we might make ourselves more empathetic people and make a more caring world.

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]