The Unsung Brilliance of Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon

So imagine if Chris Traeger were a serial killer in training ...

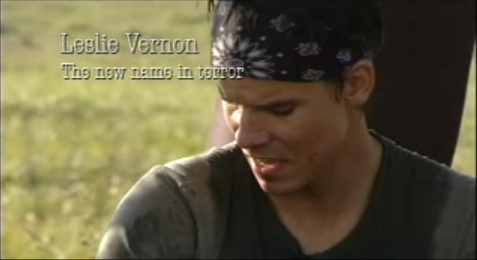

Made on a shoestring budget, released in 2006 to the festival circuit and then quietly shuffled to a small DVD release, Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon is the crème of the modern cult film crop. It’s inches from falling flat on its face in every direction (some sets were scouted in the middle of shooting, the reliance on The Famous Cameos is an eternal temptation for mugging, and the whole thing falls apart if the two leads don’t work), which makes the lean, brilliant efficacy of the film all the more breathtaking. By all rights it deserves to be the crown jewel of the meta-horror subgenre, and a top contender in horror comedy. Let me show you why.

To start, a brief plot summary: set in a universe where Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees et.al were very real serial killers and cults of personality, we follow three college students working on their thesis project: a documentary film about killer-in-training Leslie Vernon. Vernon is a gleeful, gushing fan of his craft who quickly endears himself to director Taylor and begins laying out his plan for his debut. The film’s style is mostly mockumentary/found footage in style, though it shifts to traditional 3rd person horror when Leslie’s plans are playing themselves out – not unlike watching a cast interview and then seeing a sneak peek of the finished product (it uses this setup to its advantage when the film must inevitably turn action-oriented in its final third, using the precedent set within the structure to put the audience on-edge long before certain truths sink in for the characters).

The result is an exploration of something introduced in the first “true” slasher, Halloween (putting aside the influence of proto-slasher The Texas Chainsaw Massacre): it puts us into the killer’s point of view. This is the first point where Behind the Mask branches away significantly from films like Cabin and Scream: those films have a certain archness to their meta-textuality (I have before and always will contend that New Nightmare is the infinitely better version of the concept Craven popularized in Scream), content to lean back and point out the rules of the game with a sniffy air of ‘ah yes, aren’t we all so much better than that gross formula now’ (while they themselves began to wallow in the growing pit of post-modernist horror that was rife with its own clichés).

And while that can be relevant when the subject matter is fresh (I’m an ardent defender of Spec Ops: The Line, after all), the fact that slasher films (and body count films more broadly) had been pretty dead long before either film came out, there’s something unnecessarily cruel about the whole venture (before one even touches on that particularly galling thematic issue in Cabin’s third act).

Behind the Mask comes from a place that’s willing to acknowledge that slashers did not become a successful genre from an absence of viewers, and constructs for itself a very careful balancing act of giddiness and alienation. Much of this comes down to Nathan Baesel’s superb performance as Leslie, whose effusive nerdish glee over his craft is pitch perfect for anyone who’s ever stood in line for any kind of convention. Listening to him discuss the fine details of finding a Final Girl (“survivor girl,” to use the film’s terminology), glow over the history of his predecessors, and basically ooze friendly passion from every word, one quickly forgets (for all the times it’s halfheartedly brought up by Angela Goethals’ equally excellent Taylor) that all of this comes down to chopping up unwitting teenagers.

By the time we and the film have begun to pull back from Leslie, the questions of theoretical violence versus escapism versus exploitation have all sprung up in the viewer’s mind from a character-driven place that escapes having the film look down its nose at its audience. Because don’t get me wrong, the idea of a genre that exists and continues to exist on the thrill of watching the slaughter of cardboard stand-ins for human beings is disturbing on a conceptual level. But it’s far more effective to let us as audience get lost in the appeal (and here I find myself coming back to that Spec Ops comparison) and then to bring in the nasty implications that come of playing that fantasy out.

The script is particularly adept at giving Baesel moments of childish petulance that the others aren’t ‘getting it’ alongside two or three moments of utterly nonexistent empathy that are chilling in a way that the gore effects or jump scares will never (and were not intended to) be. Those moments stick after the dark comedy and the traditional genre setpieces have gone, worth watching the entire film for partially because they only work as the culmination of the time we’ve spent in this world – they’re never going to retain their effect cut out for a ‘scariest moments’ list, because their power is their context (while I’m making endless reference points, the car-swamp scene in Psycho).

While not all satire must sympathize with its targets, the best often does (The Book of Mormon’s affection for Mormonism and ultimate sympathy for faith-as-concept comes to mind). A film like Cabin gets by quite well on Whedon’s arch dialogue, a likable cast and creative monstrosities, but its satire is unfocused (it can only really be said to be a parody of Evil Dead in any direct structural fashion, and Sam Raimi beat him to that by about 20 years) and its understanding of its genre sometimes shallow before we even get to that really huge thematic issue. Scream had the trouble of being cringingly on the nose for the sake of leading its audience by the hand, again with a genre that was pretty well dead by the 90s (funnily enough, New Nightmare was an infinitely cleverer effort on the same themes by the same director that managed a lot less notoriety. I believe I am seeing a pattern).

Behind the Mask might be a far smaller, arguably less ambitious film than either of its more famous counterparts, but it feels sharper and truer for its more focused gaze, able to wiggle into a zone of thoughtfulness without sacrificing the integrity of its narrative, its comedy, or its peculiar love and fascination for the world it created from monsters.

As of time of writing, Behind the Mask isn’t available as part of any of the subscription streaming services. It is available on YouTube and Google’s VOD, and DVDs are dirt cheap—well worth the purchase if you’re even a touch curious.

Vrai is a queer author and pop culture blogger; they’re researching ways to warp reality and replace a certain film with this one in the public consciousness. You can read more essays and find out about their fiction at Fashionable Tinfoil Accessories, support their work via Patreon or PayPal, or remind them of the existence of Tweets.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]