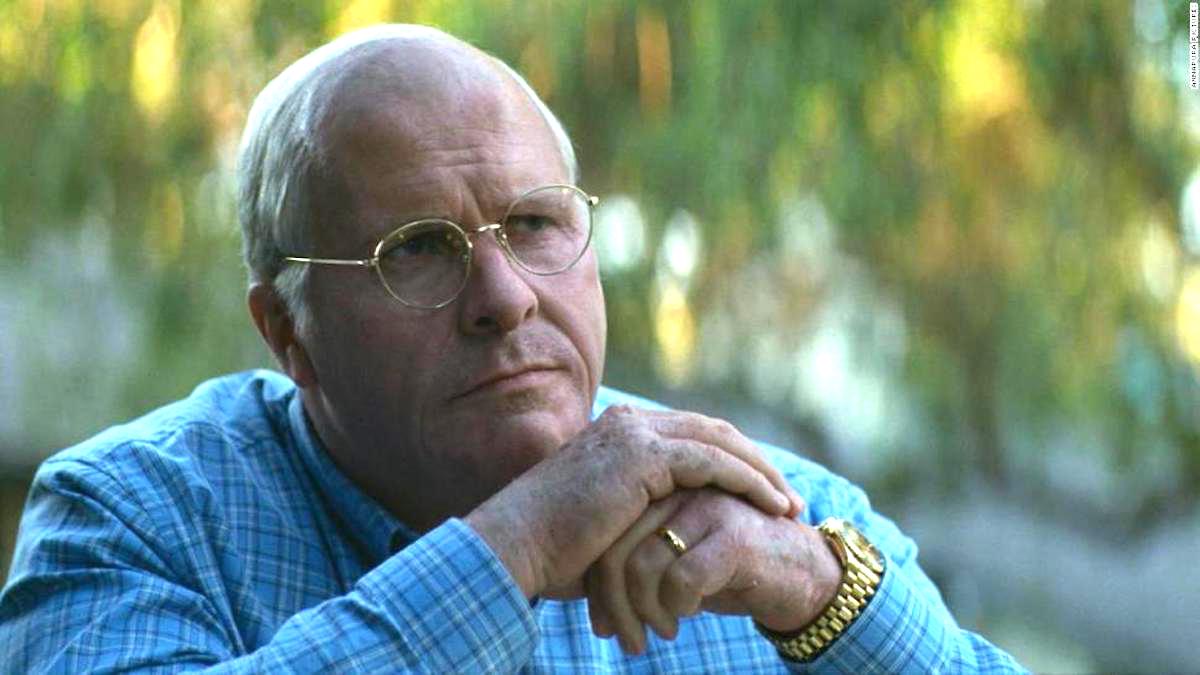

It’s been a long time since I enjoyed a movie as much as Adam McKay’s Vice while also fully understanding why so many people don’t like it. The stylized, grimly funny Dick Cheney biopic has a not-bad but not-great-either-especially-for-an-Oscar-contender 64 percent aggregated score on Rotten Tomatoes, and the critics who disliked it, like the Daily Beast’s Marlow Stern, really disliked it.

Even if you agree with the movie’s politics (and rest assured, you will know whether or not you do very early on), there may be limited entertainment value in the slow-motion dread of watching the geopolitical events you already know helped put the world and the country in its current state.

That said, my first thought when I exited the movie over the holiday weekend was that it’s the single most socially responsible movie about a male antihero I’ve ever seen. The analysis of the antihero, what he says about our culture, and whether that culture glorifies him is a cliché in its own right at this point, and to be sure, stories about bad men, real and fictional, often try to have it both ways on their subjects.

Breaking Bad’s Walter White ruins countless lives, but even as it seems he faces meaningful consequences, he gets to go out in a blaze of glory, mounting a rescue mission against literal Nazis. The Wolf of Wall Street’s Jordan Belfort and his colleagues are plainly repulsive figures, but try to find someone with a clearer memory of the scene where Belfort assaults his wife and attempts to kidnap their daughter than the movie’s extended scenes of partying and Looney Tunes Quaalude abuse.

No less a real-life bad man than Kevin Spacey clumsily attempted to tap into this paradox in December, releasing a bizarre video in which he suggested that, in being entertained by his portrayals of sociopaths, we the viewers gave him, the actor, our de facto blessing to be a sexual predator.

Vice has no time for any of this. It is never a movie about how cool it would be to be a person like Dick Cheney, Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carrell, giving maybe his best “serious” performance yet), or Paul Wolfowitz (Eddie Marsan). To the extent that the movie depicts their misdeeds, it’s not giving us permission to marvel at their theatricality or audacity, like Frank Underwood shoving a reporter under a train; it’s rubbing our noses in their consequences.

In one of those scenes that even those who share the film’s politics may find a little much, Cheney’s inner circle in the executive branch meets for dinner at what appears to be a toney restaurant while their waiter (Alfred Molina) goes over the “menu” with them—items like extraordinary rendition, Guantanamo Bay, and warrantless wiretaps. McKay’s vision of these men is less as amoral badasses and more a collection of allegorical devils in a medieval painting.

The film’s most ruthless condemnation of Cheney, however, comes in its emotional climax, taking place after Cheney has left office. One of the most common tropes for showing your antihero has a heart after all is to depict him as motivated by love for his family. Walter White is, of course, the most famous example, but there’s also Michael Corleone, The Shield’s Vic Mackey, Tony Soprano, and Don Draper. Crucially, all of these men regularly refer generally to their “family” as the most important thing, but while they’re devoted to their children, all of them are absolutely horrific husbands—their heart is specifically in being a patriarch.

At first, it seems as though that’s where Vice is going with Cheney. When his younger daughter Mary (Alison Pill) comes out to her parents, he immediately, and apparently sincerely, tells her they love her no matter what. He opts not to run for president in 2000 to spare Mary being made a campaign issue, and when he meets with George W. Bush (Sam Rockwell) to discuss becoming his running mate, he makes clear that even if Bush makes opposition to gay rights part of his platform, Cheney will have nothing to do with that.

Then, in 2014, we get the film’s most intimately devastating scene: Mary’s older sister Liz (Lily Rabe), attempting to primary Sen. Mike Enzi in Wyoming, is accused of supporting marriage equality, a potential kiss of death in the state. Cheney, the devoted father, values power even more, and gives Liz his blessing to throw Mary under the bus. She loses anyway.

In the film’s final moments, Bale’s Cheney, giving a televised interview, breaks the fourth wall and addresses the viewer directly. He sneeringly defends himself, refusing to apologize for what he’s done to “keep Americans safe,” but by placing this scene after his betrayal of Mary, it rings as hollow as it should. This man, who we just watched break his daughter’s heart for a possible political legacy, did what he did with anyone else in mind?

No, just like even Walter White was eventually forced to admit, he did it for himself, because he was good at it, and he liked it.

(image: Annapurna Pictures)

Zack Budryk is a Washington, D.C.-based journalist whose work has appeared in The Guardian, Style Weekly and NOS Magazine. His novel Judith, a feminist crime thriller, is available now, and with some luck his second book, a YA novel set during the Boston busing crisis, will be ready in 2019.

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Published: Jan 4, 2019 09:49 am