We Know The Devil Visual Novel Is an Adolescence Apocalypse

When I was nine, I went to bible camp. I had been living in Montana for over half a year, having moved there from Amsterdam, which meant virtually all my friends were Christian. One of said friends would go to this thing called Bible Camp, so in order to help bridge the magnificent chasm of a childhood summer, I went too.

My memories of that week are devoid of scripture; they mostly consist of swimming in the lake and eating cheap chicken fajitas like they were delicacies. I had not grown up in a religious family, so I wasn’t quite buying what the Good Book was selling. Instead, I enjoyed the sense of community and privately kept an intellectual distance from doctrine (I was a tiny smart-ass, but I was also smart enough to know when to keep my mouth shut most of the time). Even as a budding agnostic, I was not other enough to exclude; I was a young boy and could still be saved. I had nothing but fun at Bible Camp.

So, I could lie and say that the camp experience of the girls in We Know The Devil is also mine, that I relate to it like the Venn diagram of religiously-raised LGBTers does. I could, but The Devil does not tolerate liars.

I was a teenager though, so I can talk about that.

We Know The Devil is a visual novel by Aevee Bee, Mia Schwartz, Alec Lambert, and the folks at publishing company Date Nighto. For those unfamiliar with the term, a visual novel is like a choose your own adventure novel, but with art, a soundtrack, and better dating prospects. This one involves three teens that are trapped in a vaguely Christian Summer camp for misbehaving magical girls and also they have to fight the literal Devil at the end of the night. Bee’s writing is responsible for making you feel bad when you (inevitably) hurt someone, Schwartz’s art makes you think you would look cute drunk—if only someone would take a picture of you with a Game Boy camera—and Lambert sets the whole thing to a deliciously oppressive synth soundtrack.

To say that We Know The Devil is about something is kind of like saying a day, a summer, an adolescence is about something; you can write a narrative to make the statement true, but it feels a bit dishonest. The game certainly feels like something to me though, and to me, that something is the awkward hell of my teenage years.

In We Know The Devil, there are rules that must be followed, and authority figures are very insistent on letting everyone know that they will be punished for breaking them, yet the rules themselves are never made clear. This is true of a lot of things, obviously, but it’s as teenagers that we, that I, developed an acute awareness of how structural and unfair that is.

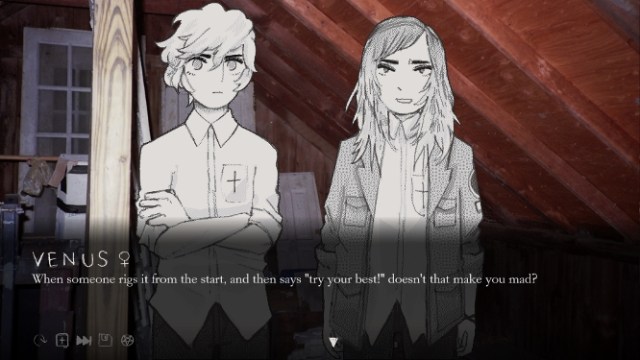

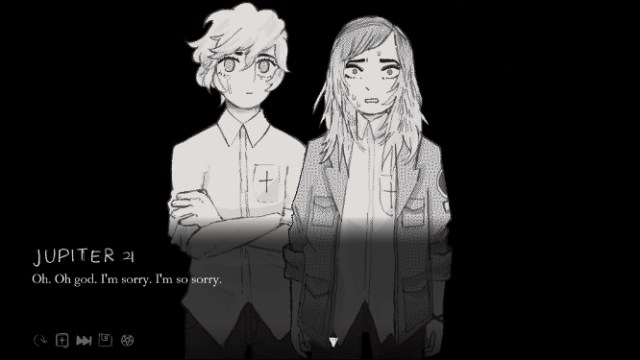

The girls of We Know The Devil are very much aware. The oppressed, on every level, are always hyper-aware of the limitations imposed upon them. This is especially true of the girls of Summer Scouts’ Group West, our heroines: Venus, Jupiter, and Neptune. Venus deals with the rules by buckling and apologizing for any perceived slight the first chance she gets; she responds to the rules by making everyone aware of just how aware she is, in the hopes that they will deem her acceptable and let her move on. Jupiter internalizes the rules; she has become so good at following them or appearing to follow them that she sort of becomes the physical manifestation of the rules and the idealization of herself. Neptune, finally, kicks and screams and swears and claws at the rules every chance she gets; she defines the rules by being opposed to them and tries to get everyone else on her side.

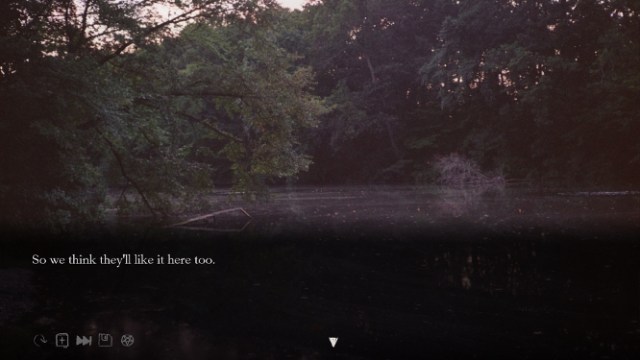

The weird, unknowable system of We Know The Devil pervades the girls’ every action, even when they are sent out of the direct purview of the rest of camp to meet The Devil. They still worry about the correct procedures and what others must think of them. They may be in a secluded cabin, but that does not undo a decade-and-a-half of behavioral training.

Nor does the visceral horror of The Devil! The bursts of static, the sirens that signal his coming (also responsible for the best audio cue in recent memory), the very act of splitting up the gang—these Satanic micro-aggressions do not replace the social terror these girls are constantly exposed to, but contribute to it. After all, it was their bullshit camp that told them to spend the night in a creepy-as-hell shack in order to maybe fight Satan, it was their bullshit society that sent them to a camp that refuses to adequately prepare them for that fight (three people does not a buddy system make), and it is still their bullshit God that tacitly approves, if not demands, this whole mess. Every spook and scare is another reason to complain about the unfairness of it all. In turn, every whinge and moan is another crack for The Devil to slip into.

In the same way, the hormonal hell we experience as teens, the constant rush of intense loves and hatreds, this only aggravates our understanding of our systemic entrapment. I had more than a few friends in high school who thought curfew was both arbitrary and a tool of oppression, though they would probably not use those terms unless they were feeling particularly dramatic or wordy.

In my own case, I let my school grades contribute entirely too much to my self-esteem, so that a low mark would send me into a spiral of self-loathing. In the game, Venus, Neptune, and Jupiter have been left feeling like worse people for falling short of the letter or spirit of the law. In the case of Neptune and Jupiter, their romance goes against everything they’ve been told was natural, so that they only feel the least bit comfortable acting upon their impulses in the darkest most private moments they share together and must bear the heartache the rest of the time. Any teen, any person, would feel resentment at the ones who were responsible.

The truth is that the power trio don’t really fit into the world of We Know The Devil at all. No really, the shack where they have to face The Devil is literally 2/5ths too small for them. There is no room for Venus As a Girl or a mythologically incestuous lesbian power couple in God’s world, so they are left to pick at their bodies as much as they pick at their surroundings. Their discomfort in this case is subtle and typically teenage, hyper-aware of their surroundings and the people in them, but possessing very little awareness of their own issues. Venus doesn’t even realize her discomfort with her assigned gender until she sheds her human form altogether.

The girls of Group West talk about their frustrations like they are things that will end with Summer Scouts. They just have to bear it until then, quietly or not. For some of us, for me, that was true: we grew out of our teenage issues when we grew out of being teenagers. If you can’t though, the system has no real place for you. Adults that don’t fit the system are dysfunctional and teenagers are distrusted until they do.

So Group West is kidding themselves then. They may have a future in God’s world, in the Real Scouts (the one where the buddy system works and you get transformation sequences), but only as deeply compromised selves. That future is one where others will hate who they really are, where they will hate themselves for who they really are. Already figures of authority—The Bonfire Captain, God—are teaching them to look for evil in each other or The other, The Devil, not in the system. In the mean time, those same figures of authority assume the worst of their charges.

Like most bogeymen, The Devil is oh so very weak. In the first three endings, there is only one girl that falls to her clutches. It is the girl that was excluded, while the other two drew comfort from one another. Without support, The Devil, one of the sweet girls from Group West, is unleashed: her emotional wounds become physical power and she loses human form. The change is framed as a corruption, as a magical girl becoming a terrible witch, if you’ll allow me a reference. To their credit and their failure, the two never believe it could have been her.

Yet one girl is far from unstoppable, even if she is The Devil. It is because they are together that they can fight against the third and drive her off. It is because they are together that they can weather God’s kingdom and convince themselves it is good. It is because two of them drew closer together that they did not notice the third hurting as much as she did. Friendships are a powerful tool for survival, but if you’re not careful with them, they can also be a trap: a little bit of honey that convinces you your situation might not be so bad after all.

The Devil is gone by morning light. She might be alive (although Ms. Bee had to personally assure me of such before I believed it), but she is not a part of the ending. Two are together and the third got hurt. Depending on who those two are, you might be okay with that, you might not be. I can tell you that, as a teen, I was usually the third.

These three endings are a reminder of the sacrifices our relationships imply, that the happy outcome is hard, especially if we take the premise given to us at face value. They are a reminder that, unless deliberate action is taken, one relationship will come at the cost of the other.

The Devil pulls a mean trick by only taking one girl per ending. She takes the blame. She makes us hate her for turning us against a girl we loved, for turning one of them into a monster. She remains other, to two of the girls and to us, because what sane individual would trust THE DEVIL? But the tragedy of those endings is not that a girl becomes The Devil; the tragedy is that a girl is lost to us, to her friends. “There’s room for three in my world” The Devil says, “and only two in His”. If they could all become The Devil, then everything would just be fine and dandy, wouldn’t it?

So, in the fourth, final ending, that’s what they do. They all become The Devil and they create literal Hell on Earth. And the jerks from South Campus join them, all the kids do. Of course those kids hated God’s world too! They were mean to the girls precisely because of how they embodied its rules to them. All the other kids are in the Summer Scouts instead of Real Scouts for the same reason Jupiter, Neptune, and Venus were: they were the problem youths that needed a correctional measure. Banding together and rallying against authority is scary enough when there’s only people to worry about though, much less when capital-G God is involved, so they make enemies of the least powerful people that still represent that other to them. This is, in the most abstract, how cliques are formed in high school. This is how social change consumes itself.

It is said against anarchism and chaos that they are defeatist, including by myself. If there is a better order possible, why throw all the good out with the bad? But in We Know The Devil, everyone is happy in Hell, at least everyone we care about, and the order sucks. You would think that God being indisputably real would make organized religion less prone to farce, but His presence changes nothing. It only makes the question—“If God hates The Devil so much, why doesn’t He stop him”—all the more salient. What little we hear from God in the game is an accusatory sermon that is meant to turn friend against friend. The Devil is nothing but nice and welcoming (although that is also always the danger).

The Devil is many things. That’s part of her deal, even in this game. One of the things she is here though, is a sort of adulthood. The Devil’s adulthood is the one denied to them by the system, by God. Everyone finally gets to cast off their terrible adolescent bodies, along with all their discomforts, and free themselves from the horrible institution that kept them against their will. For me, this was graduating high school and going to college. High school was my real Summer camp and even after all these years I am all too happy to be free of it. For the Summer Scouts, their graduation into adulthood meant transforming into demonic hellbeasts. If anything, they are luckier for it; by freeing themselves of God Himself, they free themselves of all systems, something none of us have the luxury of doing, comfortably or not.

So I guess what I’m trying to say with all this is: The Devil’s alright by me.

I wonder what the counselors at Bible Camp would have thought of me saying that?

You can buy We Know The Devil here for $6.66 and maybe also your soul.

Alexander Smit spent most of his philosophy major thinking about movies and food. You can find his writing on kantianbioethics.tumblr.com and his stream of consciousness on Twitter.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]