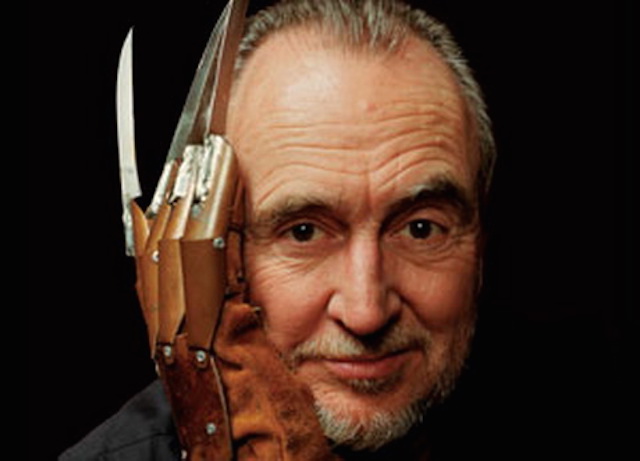

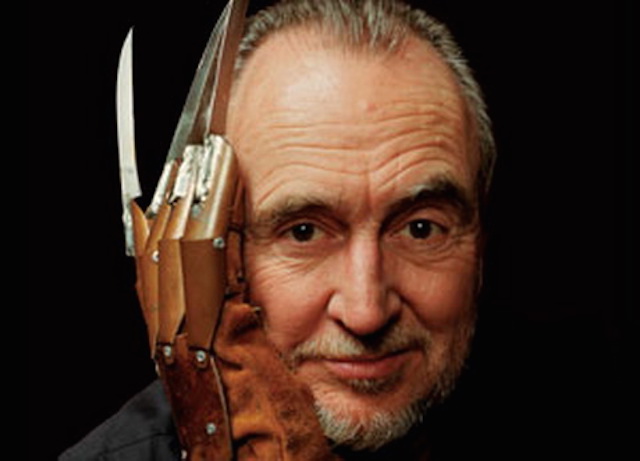

How Wes Craven’s Influence Made Horror Movies More Subversive

Iconic horror director Wes Craven died at 76 of brain cancer last weekend, a bit of sad news that broke at the same time Nicki Minaj was giving Miley Cyrus a richly-deserved tongue-lashing at MTV’s Video Music Awards. The immediacy of the VMAs meant it took a day or two for tributes to Craven to trickle in, which had the positive impact of longer, more considered writing about what Craven meant for the horror genre.

Craven’s influence is hard to overstate; he made his mark in three consecutive decades, with low-budget exploitation fare like The Hills Have Eyes in the ‘70s, the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise in the ‘80s (and beyond) and Scream in the ‘90s. Those latter two have gotten most of the ink in discussions of his legacy, and they exemplify what truly set his films apart: their subversiveness and their self-awareness. Scream, in particular, was like something the genre had never seen before—a horror film whose protagonists-cum-victims were familiar with the horror genre and its tropes and lived or died based on that knowledge. But two of Craven’s comparatively overlooked films demonstrated that subversive streak—and Craven’s expert satirical mind—even better.

1972’s The Last House on the Left comes up surprisingly little in modern discussions of horror film, but it sparked a full-blown moral panic upon release, with its no-budget home-movie style prompting rumors it was in fact an actual snuff film. It tells the story of two teenage girls who attend a rock concert and, on the way home, like Red Riding Hood, stray from the path to score some weed. This leads to their rape and brutal murder by vicious ex-con Krug Stillo and his equally depraved entourage (it should be mentioned that said entourage including a predatory butch lesbian has not aged well at all).

The horror genre, Stephen King once wrote, is innately reactionary, preying on fears of the evil outsider entering communities and lives uninvited. At first, that seems like exactly what Craven is doing here. Krug, with his charisma and hippie-ish affectations, is an obvious stand in for Charles Manson, who’d been convicted only a year before (although weirdly enough, the film is an acknowledged loose remake of Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring). “Mothers, keep your girls at home,” to quote Nick Cave, appears to be Craven’s message.

It’s in the film’s third act that all of that is turned on its head. After the murders, Krug and his gang have the remarkable bad luck to seek shelter at the home of one of their victims’ parents. When they put two and two together, the parents unblinkingly and brutally take their revenge. This sounds like it could be part of the same reactionary fantasy—the conservative traditional family unit meting out justice to that which violated it—but the way Craven shoots it, it’s not remotely triumphant.

Instead, it’s the same sickness that their victims represent infecting them. The film’s violence was so controversial that its purpose—to warn against the spirit of paranoid, right-wing vengeance that had taken hold in Death Wish-era America—was almost completely lost in the shuffle. (Craven revisited the same theme in the Nightmare franchise; in life, Freddy Krueger was a child-murderer burned alive by the parents of the seemingly normal, wholesome community.)

Nearly two decades later, Craven, who had made The Hills Have Eyes and Nightmare in the interim, got even more overt with his political commentary in 1991’s The People Under the Stairs. Even before the horror sets in, this is not your father’s horror movie: our hero is Fool, a young black boy from the Los Angeles projects, rather than the typical array of middle-class white kids. In contrast to King’s description of the formula, Fool is the invasive force in this story, bullied into helping a local petty criminal burglarize the house of their wealthy slumlords.

At this point, the story becomes a balls-out insane amalgam of “Hansel & Gretel” and political satire; the slumlords are a vicious, cannibalistic brother and sister who call one another “Mommy” and “Daddy,” just like Ronald and Nancy Reagan, and keep a pack of starving, deformed semi-feral children in the basement and (you guessed it) under the stairs. And Craven isn’t done playing with our expectations; even after he’s (accurately) cast white suburbia and the Reagans as the epicenter of evil; the titular people under the stairs prove to be Fool’s allies. It might be the first horror film named after its victims. The film’s climax, in which Mommy and Daddy’s long-abused tenants gather in front of the house to confront them, is like watching Les Miserables on shrooms, and you will love every second of it.

There’s a lot more on Craven’s CV that demonstrates these same instincts—like 1988’s The Serpent and the Rainbow, which sets a zombie story against the backdrop of Haiti under the iron fist of Jean-Claude Duvalier, or 2005’s severely underrated Red Eye, which wrings its scares not from gore but from Cillian Murphy and Rachel McAdams’ stellar central performances—but really, Craven’s desire to set fire to convention came through in just about everything he made, with the possible exception of 1999’s Oscar-bait Meryl Streep-starring Music of the Heart, a combination of elements that is as weird as it sounds. Craven was, above all else, a true original, and, far too uncommonly among horror filmmakers, understood that the genre is about more than giving us what scares us—it’s about examining why it does.

Zack Budryk is a Washington, D.C-based journalist who writes about healthcare, feminism, autism and pop culture. His work has appeared in Quail Bell Magazine, Ravishly, Jezebel, Inside Higher Ed and Style Weekly and he recently completed a novel, but don’t hold that against him. He lives in Alexandria, Virginia with his wife, Raychel, who pretends out of sheer modesty that she was not the model for Ygritte, and two cats. If you don’t think Molly Solverson from “Fargo” is the best he will fight you. He blogs at autisticbobsaginowski.tumblr.com and tweets as ZackBudryk, appropriately enough.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]