The Age of Misanthropic Villains- Why Do We Like Them?

"The status is not quo. The world is a mess and I just need to rule it"

There’s a lot to lament about Fantastic 4’s financial and critical failure, but to my mind its greatest disappointment was easily its villain, Victor Von Doom, simply because his character had the most wasted potential.

Early on, Victor argues that, though inter-dimensional exploration may hold the key to saving humanity, maybe humanity doesn’t deserve to be saved. Maybe we, as a species, have done so much wrong that we deserve annihilation. The movie, being the train wreck that it is, does nothing interesting with this misanthropic statement but it made me realize that the irredeemable wretchedness of humanity has cropped up in quite a few villainous manifestos recently.

Loki may be “beyond reason” in The Avengers but he’s not wrong when he says “the humans slaughter themselves in droves” and that we’re “made to be ruled.” In the sequel, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Ultron’s programming leads him to conclude that saving the world entails destroying humanity and even Mjolnir-worthy Vision concedes that our species is doomed.

In Dawn of the Planet of the Apes, Koba (another Toby Kebbell character, interestingly enough) is so unquestionably justified in his hatred for humans that he isn’t framed as a villain until he turns against his fellow apes.

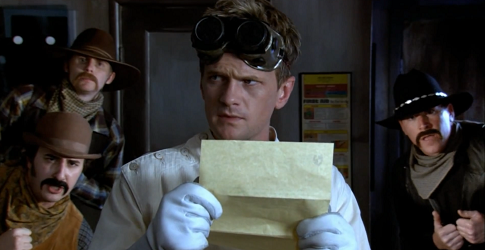

Dr. Horrible may be the protagonist of Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog, but he’s a bad guy within the universe of the series who plans to make the world a better place by overthrowing the establishment and “cut[ting] off the head … of the human race” (it’s not a perfect metaphor).

It’s also worth noting that many of these villains became fan favorites. So, what is it about eloquent misanthropy that we find so compelling in our bad guys?

Well, in its most basic form, the conflict between the hero and the villain is a struggle to preserve the status quo … or return the world to a previous, “better” status quo.

There are exceptions, of course. Gilgamesh and Enkidu seek out and kill Humbaba for glory and the Baron, Baroness and Child Catcher of Vulgaria are overthrown in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. Overwhelmingly, though, the premises of stories with an identifiable protagonist and antagonist entail the baddie mucking things up and the hero pressing the reset button: villain tries to take over earth, hero ensures that current governmental systems remain enact. Villain steals money, hero returns it. Villain usurps the throne, hero overthrows him/her and keeps the chair warm until the rightful ruler reclaims it.

Admittedly, the status quo is usually preferable to what the villain has planned (life under Emperor Palpatine wouldn’t have been pleasant) but this knee-jerk assumption that it’s the hero’s job to keep things the way they are indicates a level of satisfaction with the status quo that I’m not certain many people feel anymore.

Sure, the twist that humans are the real monsters has been around for a long time, but until relatively recently the concept was confined to speculative fiction. To see villains spout such rhetoric in summer blockbusters (and beloved viral satirical superhero musicals…) and for fans to take these antagonists to their hearts suggests that, in this Information Age in which we live, the atrocities taking place at any given time on this planet are impossible to shut out entirely. Maybe that’s made us more open to the possibility that we, as a species, aren’t all that great, that rooting for the protagonist to thwart the villain’s attempt to change things is to overlook how deeply troubling our status quo is.

Of course, one could argue that framing the misanthropic characters as villains undermines this aforementioned self-awareness … but I choose a more optimistic interpretation.

When these stories are well told, the heroes acknowledge the problematic nature of the status quo but nonetheless reject the villain’s “solution” that humanity deserves enslavement or annihilation. By making the villain the embodiment of cynicism and the hero a stubborn optimist, their conflict becomes, not a struggle for the status quo, but for hope.

In Fantastic 4, Franklin Storm counters Victor Von Doom’s declaration of mankind’s worthlessness, not by arguing that humans haven’t made a mess of things but by insisting that the story doesn’t have to end there. “The failures of my generation are the opportunities of yours,” he says.

More poignant is Vision’s final conversation with Ultron in which he admits that humans are doomed but adds that “a thing isn’t beautiful because it lasts. It’s a privilege to be among them.”

These aren’t wide-eyed idealistic heroes who see the world in black and white, but men and women who, despite compelling evidence to the contrary, are holding onto the conviction, as Samwise Gamgee puts it (though The Lord of the Rings is about as morally stark as you can get) “that there’s some good in this world … and it’s worth fighting for “

Petra Halbur is a writer traversing the perilous terrain of post-graduate life whilst trapped in the world-building phase of developing her science-fantasy graphic novel. You can read more from her at Ponderings of a Cinephile or follow her on Twitter.

—Please make note of The Mary Sue’s general comment policy.—

Do you follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]