I write this post going into science fiction as a fan, but also unaware of how most scientists think about it. I can imagine two central viewpoints: (1) scientists who enjoy it (like myself), simultaneously as entertainment and a bit of critical thinking and (2) scientists who dislike it due to its tendency to portray “evil scientists” and/or science and technology gone awry, destroying the world.

I didn’t really grow up reading science fiction. Sure, I was (and am) completely obsessed with some fantasy novels (e.g. Lord of the Rings) but never made the leap to becoming a true sci-fi nerd. It wasn’t until I started studying science more fully that I developed an interest in speculative science fiction. Many of the stories do deal with technology taking over civilization – but embedded within this framework is a great deal of excitement, along with some deserved anxiety.

The best way for me to explain these conflicting emotions is with an example of something that happened to me in the past few weeks. We are slowly inching closer to developing lab-produced organs, which would be incredibly beneficial for a lot of obvious reasons. Just this month there have been developments toward mass-produced red blood cells, as well as bioartificial lungs. Eerily, I read about these discoveries as I was tearing my way through Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, a speculative fiction novel about a bio-engineered future, including “pigoons” (pig/balloon) that have grown to massive sizes in order to grow 6 kidneys at a time for organ harvest, and “ChickieNobs,” a fast food product made from transgenic chickens that have no brains or beaks and grow 8 chicken breasts at once. While reading, I simultaneously was in wonderment about how we could be reaching the ability to actually engineer these creatures, but obviously nervous about the implications described in the novel. (No spoilers here!)

Some scientists might write this kind of anxious thinking off as trash. “We’re trying to develop organs to save lives – we don’t need a bunch of crazies trying to stop us in order to avoid a hypothetical bioengineering apocalypse!” But scientists are born and raised to be skeptical – and that’s all that much of this writing is. Being skeptical about the pure goodness of scientific advance.

But more importantly, science fiction is one of the ways that non-scientists absorb science. Oryx and Crake is a national bestseller, suggesting that millions of people have read Atwood’s tale of bioengineering gone wrong. While we should assume that the public knows that this is fiction and doesn’t take it entirely seriously, these stories do raise questions about the potential misuses of science that might not be as prevalent otherwise. I believe that scientists have a duty to communicate with the public. (Not all scientists agree with me on this.) By knowing where non-scientists are coming from, scientists can better address some of the potential issues that might be raised by their achievements.

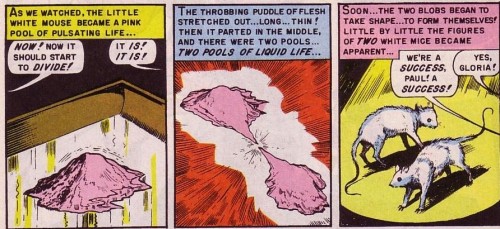

EC Comics’ “Weird Science” #6 (1951)

Sci-fi also provides a venue for discerning how our ways of thinking about science have developed historically. One of my favorite time periods for sci-fi is the 1950s: It was a time when just enough was known to speculate wildly, but not enough to fully disregard these speculations. After all, Watson and Crick did not discover the DNA structure until 1953! Thus you have the birth of many of our superheroes, variously mutated by “cosmic rays” or radiation, altering their molecular structures and giving them superpowers. We had just enough pieces to wonder, but not enough to know the full picture.

And sometimes, the stories told as fiction end up being today’s truths. Reading stories that feature the scientific dreams of these writers, and knowing that they’ve come true, can be heart-wrenching. In one of my favorite short stories, “The End of the Beginning” in R is for Rocket, Ray Bradbury describes a couple gripping their seats with excitement and nervousness as their son boards a shuttle – the first shuttle to land on the moon. This collection was written in 1965, 4 years before Apollo 11 landed on the moon. Bradbury’s description is incredible:

All I know is it’s really the end of the beginning. The Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age; from now on we’ll lump all those together under one big name for when we walked on Earth… Millions of years we fought gravity. When we were amoebas and fish we struggled to get out of the sea without gravity crushing us. Once safe on the shore we fought to stand upright without gravity breaking our new invention, the spine, tried to walk without stumbling, run without falling. A billion years Gravity kept us home… That’s what’s so really big about tonight … it’s the end of old man Gravity and the age we’ll remember him by, once and for all.

Gives you shivers, eh? Of course, this day has come and gone in real time. We are still constrained by gravity, we haven’t set foot on a planet beyond the moon. But these science fiction stories can bring us back to that time of wonderment, help us to experience a feeling we missed: the great excitement of space potentially conquered. And although it didn’t happen quite the way Bradbury described it, we can pretend for at least a little while.

Science is about that excitement. About that drive to discovery, about idealism and hope. It’s easy to forget that, working away at my lab bench, pipetting DNA into tubes. Now we know a little more about science – enough that we no longer dream of mutated superheroes. But we still dream about the day when we’ll make our big discovery, solve our own scientific problem.

Science fiction can remind us of this wonderment and hope. But it also sends us a warning – to think about the potential implications of our findings, beyond our idealistic dreams. While those implications might not be as exciting as a science fiction novel, they exist, and scientists should be aware of them.

With that, I’ll leave you this quote from David Brin from Nature‘s series of interviews with science writers this past winter.

Science fiction is badly named — it should have been called speculative history… Whether you are in a parallel reality or exploring the future, it is all about the implications of change on human lives. The fundamental premise of sci-fi is not spaceships and lasers — it’s that children can learn from the mistakes of their parents.

Hannah Waters is a scientist and aspiring science writer from Philadelphia. She blogs here and tweets here. This post originally appeared on her blog Culturing Science.

Published: Jul 21, 2010 12:40 pm