When the computer is addressed in many science fiction shows, it often replies in a female-coded voice. From Majel Roddenberry’s Federation computer voice in the Star Trek series to the sentient ship AIs in Andromeda, Killjoys, Dark Matter, Outlaw Star, and Mass Effect, artificial intelligence has been a science fiction regular since at least the 1960’s. There are male-coded AIs as well—J.A.R.V.I.S., Hal, that weird Haley Joel Osment-bot from A.I.—but women have been part of humanity’s relationship with electric computers since the very beginning.

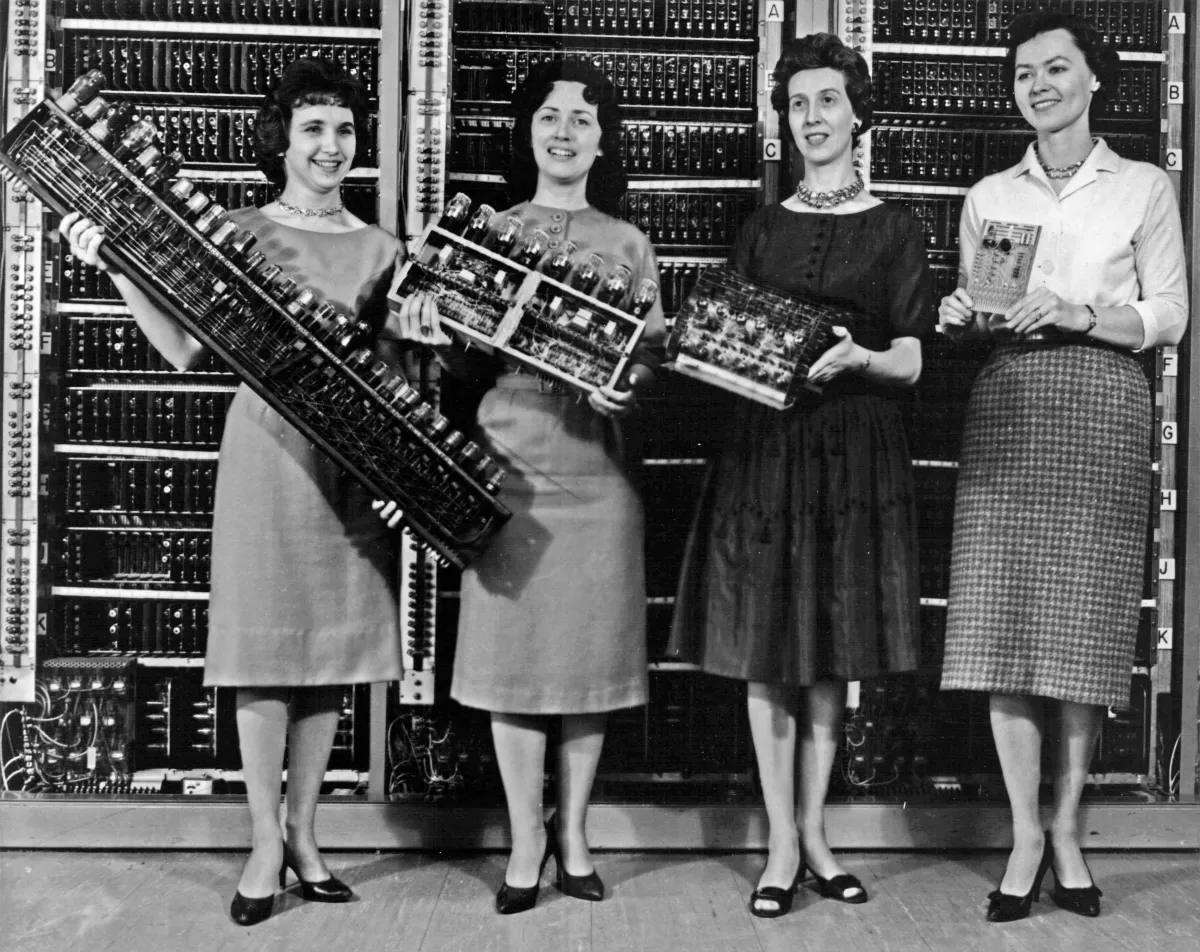

Jennifer S. Light’s article “When Computers Were Women” discusses the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) project during World War II, and how the people doing the actual computational tasks were a group of civilian and military women. The women were actually the “computers,” and were creating a machine that would someday replace them. The concept of the women as the actual computers made me think about how many artificial intelligences, whether in android form or integrated into actual ships, are coded female.

Light’s article also pointed out that history buried these early female computers. Their work was made light of, devalued, and all credit was given to the male inventors of ENIAC, reducing them practically to “ghost in the machine” status. This is where my mind made the connection. So many computer and AI characters are coded female because even layers of sexism and inequality still can’t erase the connection between the first “computers” being women and the task of computing. You can take the woman out of the workplace, but you can’t take the woman out of the machine she helped create.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m not anti-robot. I’m almost always that person who reads another doomsday/playing God/robot overlords-fearing post on Facebook with an eyeroll and a cry of “Uncanny Valley be darned to heck—create, people!” I like robots, androids, AIs, and I don’t have any fear that the Roomba is going to revolt and flatten the cat. As a matter of fact, many robotic characters are my favorites: I will always love Rommie, the android body of the ship Andromeda. She was fierce, sarcastic, protective, and could change the color of her hair at will. Who doesn’t want that? But while I love AI characters, I have to acknowledge the patriarchal history that led many of them to be created.

“Why is AI female?” asks Monica Nickelsburg’s April 2016 article for GeekWire, dividing the potential reasons for predominantly feminized AI into three major areas. Nickelsburg asks if service, sex, or adoption lead to the feminization of computers and AI characters. Ultimately, she concludes that they are all three intertwined with society’s views of women, both positive and negative.

There are other theories out there. Studies have shown that both males and females respond more positively to a female voice, perhaps explaining why Siri and other similar apps have female voices. One article made the claim that Americans respond to a female voice because we are a loud people and a feminine voice is more soothing, while the English are quieter and respond better to authority, explaining why in England, Siri has a man’s voice. More troubling, are comparisons between the assistant-type work performed by Siri and her compatriots, and tasks usually associated with secretarial work long associated with women. Nickelsburg explores this idea further:

“Assigning gender to these AI personalities may say something about the roles we expect them to play. Virtual assistants like Siri, Cortana, and Alexa perform functions historically given to women. They schedule appointments, look up information, and are generally designed for communication.”

I feel like there is definitely a divide between the AI personalities like Siri and Cortana, which provide secretarial tasks, and the mostly female AIs that control and embody a ship. And, it should be stated, that I perform secretarial tasks at my job, so I have nothing but respect for that profession. The context that is relevant to this topic is more that secretarial work is stereotyped as feminine and often paid less than similar tasks performed by men.

Additionally, there is a long historical record of referring to ships as female, which is the sort of grounding, ancient “fact” that lends a sense of gravitas to futuristic science fiction space opera. It’s like they’re saying, “See? Lots of things have changed, but not everything. The tradition of referring to ships as female has endured.” While Siri provides secretarial functions for the most part, Rommie (played by Lexa Doig) embodied a starship with strong fighting capacity. She was the ship, its codes, and everything at its powerful disposal. She was able to develop a distinct personality and had differing levels and types of interest in the various members of her crew.

via Global TV

On the SyFy show Dark Matter, the ship has an AI who is simply referred to as “The Android,” which would seem callous except for the fact that the entire crew lacks memory of their real names and identify themselves via numbers. Like Andromeda, The Android (played by Zoie Palmer) is the ship, but also has a physical android body with which she can interact with the crew and assist with the physical work of running the ship. I want to note that The Android’s clothing is much less sexualized than Rommie’s plunging neckline; and also note that on Dark Matter, most of the characters’ clothing is form-fitting, giving The Android a more conservative appearance than many of her crew.

via SyFy

Other examples, such as Melfina from Outlaw Star, who was a synthetic being created to meld with the ship, and EDI, the AI from the Mass Effect game series, provide extreme bookends for AI coded female. Melfina, as cool as she was and as much as I love that show, was pretty sexualized. She got naked to do her thing with the ship, whereas EDI has a female voice, but is represented by a holographic circle on a stick, only vaguely reminiscent of a human head.

On Killjoys, another SyFy series, the main female character, Dutch, owns a ship with an AI named Lucy, voiced by Tamsen McDonough. Lucy has her own personality and shows a slight preference for Dutch’s trainee John (which makes sense, as Johnny treats Lucy more like a person than Dutch does and has more tech expertise.) The relationship between Johnny and Dutch is very reminiscent of John and Aeryn from Farscape, only without the romantic entanglement aspect. Johnny and Dutch love each other, but in a more familial, platonic way. Lucy, unlike Andromeda and The Android, has no physical form. In one episode of the show, her consciousness is uploaded into an android body, and she expresses the need to “collect data” while in this unique circumstance by kissing Johnny. This was a one-time situation and has not be repeated on the show since then, whereas Andromeda’s crush on her human captain and her engineer’s unrequited affections figured regularly into the plot of the show. Nickelsburg’s (2016) article also addresses the sexualization of the robotic, citing a quote from GigaOm lead researcher Stowe Boyd, wherein he, “predicted that sex with robots will become prosaic by 2025,” and stated that, “Robotic sex partners will be commonplace, although the source of scorn and division, the way that critics today bemoan selfies as an indicator of all that’s wrong with the world.”

via SyFy

As a prolific and unapologetic selfie enthusiast, I particularly enjoy that quote and the notion that the new “obnoxious” tech behavior of the future might be robot sex. Where this becomes a little bit problematic is in the imbalance of oversexualized female bots and the relative lack of depictions of sexualized male bots. I mean, I loved Gigolo Joe from A.I. He might have been the only thing in that movie I actually did love, and it certainly didn’t hurt my eyeballs that he was played by Jude Law, but this is one example of a male sexbot in a world full of examples like Her, the Buffybot, and Ex Machina. Often, male AIs are associated with fear and control, like Hal and Ultron, where female AIs could connote a more people-pleasing image. While this makes some manufacturers’ choices more understandable, it does reinforce the stereotypes of service, sex, and agreeableness that have been problematically associated with women and computers since the days of the first computers: human women.

featured image via

Want more stories like this? Become a subscriber and support the site!

Sara Goodwin has a B.A. in Classical Civilization and an M.A. in Library Science from Indiana University. Once she went on an archaeological dig and found awesome ancient stuff. Sara enjoys a smorgasbord of pan-nerd entertainment such as Renaissance faires, anime conventions, steampunk, and science fiction and fantasy conventions. In her free time, she writes things like fairy tale haiku, fantasy novels, and terrible poetry about being stalked by one-eyed opossums. In her other spare time, she sells nerdware as With a Grain of Salt Designs, Tweets, and Tumbls.

—The Mary Sue has a strict comment policy that forbids, but is not limited to, personal insults toward anyone, hate speech, and trolling.—

Follow The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google+.

Published: Sep 26, 2016 12:01 pm