Director Of X-Men Documentary Talks About How Chris Claremont Made Socially Conscious Heroes

The Mary Sue Exclusive

Rogue. Shadowcat. Mystique. Emma Frost. If you’re thinking of a an iconic female character from the X-Men (or just a certain ragin’ Cajun), chances are, you’re thinking of a Chris Claremont character. Claremont, whose legendary run on the X-books spanned over 16 years (from approximately 1975-1991) and many of our childhoods, is also responsible for many of the series’ famous — and now, movie adaptable — story arcs, including “Days of Future Past,”and “The Dark Phoneix Saga.” He’s the man responsible for turning Wolverine into the fan favorite that he is, and for bringing the X-Men back to life after their initial near-commercial-death in the 1960s. Now, Claremont’s the subject of a new documentary, Comics in Focus: Chris Claremont’s X-Men, from the same team that brought us Grant Morrison: Talking with Gods, and Warren Ellis: Captured Ghosts. No strangers to the subject of women in comics, they’re also the ones currently in production on She Makes Comics, a new doc that will focus on exactly what it says on the tin, women who make comics, both in independent circles and in the larger industry.

We took a few moments of director and editor Patrick Meaney‘s time to talk about the importance of female characters to Claremont, what makes his run on X-Men so memorable, and how that decade and a half shaped the way we still look at comics from the Big Two today.

The Mary Sue: After working on documentaries that focused on Grant Morrison and Warren Ellis, you’re now looking at Chris Claremont’s run on X-Men. Where did the idea come from to tell Claremont’s story in particular?

Patrick Meaney: I actually first got into comics reading reprints of Claremont’s X-Men. I read the Essential X-Men books, and started at the very beginning with Giant Size X-Men #1 and went through #150 or so, which was all that was in print back then. A few years later, I hunted down the rest of his run and read the whole thing through and what struck me was how amazingly cohesive a work it is, considering it was produced on a monthly basis for seventeen years in the face of a huge amount of change in comics, both at the corporate level for Marvel and in the market itself. Claremont’s X-Men is the bridge between the Silver Age of comics and the modern era, between Stan Lee and Jim Lee, and it’s always fascinating to look at works produced in times of great change.

I looked online for meaningful writing about Chris’s run, but there was very little. There were X-Men fan sites, and a bunch of talk about “Dark Phoenix” or “Days of Future Past,” but no one was looking at this as a single work, a 200 issue statement, and I found that kind of frustrating. I think in the same way that Star Wars has become such a phenomenon and a piece of pop culture, it can be hard to look at it as a movie, X-Men has become so huge, it can be hard to think of it as something that came largely from one writer and his collaborator’s brains.

So, I decided to go back and talk to the people who made it happen and find out how a third-string Marvel title could become one of the biggest franchises in pop culture history.

TMS: I’ve read that Claremont went to Bard College, where he studied political theory and acting. How did he end up becoming involved with Marvel?

PM: Claremont wasn’t much of a comics reader as a young man, but his family were friendly with Al Jaffee at Mad Magazine. He sent Chris over to Stan Lee, and because he would work for free, he was eagerly welcomed as an intern. I think it tells you a lot about the vibe at Marvel back then that they were so eager for free help. I don’t think you’d have the same luck today getting in so easy.

TMS: How do you think Claremont’s background in political theory influenced his decisions in writing X-Men?

PM: The most obvious influence is drawing on history to flesh out Magneto’s backstory. Magneto as a child of the Holocaust is such an important piece of the X-Men universe that it was the very first scene of both the first X-Men film and X-Men: First Class, but before Claremont, that was not a component of the character. Particularly during the Romita era, Claremont engaged in a lot of questions about race and gender identity, and decades before it became a priority for most creators, he was presenting globally diverse casts in both the main title and New Mutants. Even his more recent work has featured lot of global characters, so I think his political theory background influenced a more global view than a lot of people.

TMS: Claremont is known for his creation and depiction of complex, strong female characters. Where did the impetus for these depictions come from, given the norms in comics at the time?

PM: We asked Chris about this and he said that it was largely due to a frustration with the way that most female characters at the time were presented as just ‘the girl,’ the accessory to the male heroes, or someone for men to fight over. There was a lot more potential with characters with agency and excitement of their own, and you can see the way he turned Jean Grey, a classic ‘the girl’ character into one of the Marvel Universe’s biggest players with the Phoenix Saga. I think working with Louise Simonson and Ann Nocenti on the title also helped with creating these characters. As you see in the film, they were Chris’s two biggest, most consistent influences, and that’s not the norm for most comics.

If you ask most people to name their favorite female characters from Marvel or DC, odds are they’re naming characters that Chris created or defined.

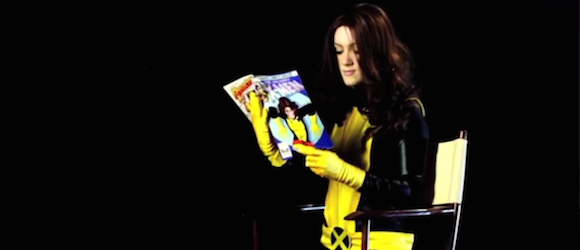

Here’s an exclusive preview of some of the documentary’s interviews with female fans and creators who came to comics through Claremont’s X-Men:

TMS: How did clashes with editors ultimately influence the trajectory of the series?

PM: This was one of the most fascinating things for me, to look behind the curtain and see the freedom that Chris had to tell his own stories, and also the way that he eventually found it hard to do so. Working with Louise and Ann gave Chris a lot of free reign, and particularly with Ann, to experiment and push towards a more modern storytelling style.

On a higher level, Jim Shooter was crucial in developing the death of Dark Phoenix storyline, and generally seems to be a respected, if combative ally for Chris during his years in charge of Marvel. As time went on, the book became so big, and Marvel became more profit driven, and he had a lot less freedom, which ultimately led to him leaving the title shortly after X-Men #1 in 1991.

TMS: Do you think this change to more heavy editorial control of storylines continues today throughout the industry? Has it been for good or ill?

PM: Good editors can make an amazing influence on comics. Without Ann’s influence, I don’t think we’d have a lot of Chris’s best stories, and without Karen Berger’s vision, we probably wouldn’t have The Sandman, Swamp Thing or a lot of other seminal titles. However, the idea of stories coming down from the top, rather than being developed by creatives has consistently produced shoddy results. Look at the X-Men titles of the 80s under Chris and Louise vs. the tangled mess of the editorially driven 90s books and you can see what happens when stories come from profit motivated executives.

I think it’s great to have internal consistency among the books, and risk takers greenlighting books, but micromanagement doesn’t lead to great comics.

TMS: What do you think is the key to Claremont’s run’s accessibility?

PM: More than anything, I think it’s the characters. He created fully realized characters who developed over time and went on real journeys. That’s always going to be fascinating to watch. We all know that the hero is going to survive this month’s cliffhanger, but when Claremont was writing, we didn’t know how they would be changed by what happened. Even in his early issues, which can feel a bit dated at times, you’re hooked by the interaction between the characters, and the slow layering of plots over time. Chris talked about how he was trying to write stories about the characters’ lives, not their adventures, and that’s what keeps them accessible all these years later.

TMS: What, in your opinion, has been the lasting impact of the long plots, large cast dramas, and developed dialogue that are characteristic of Claremont’s run on the book?

PM: I think the impact has been massive. In comics, Claremont set the template that pretty much every new superhero comic of the 80s and 90s followed, be it Teen Titans or most of the early Image titles, and he directly inspired Alan Moore, and helped bring a maturity to comics in his 80s work that elevated the whole medium. His level of serialization came about by acknowledging for the first time that comics were not a disposable medium that turned over readership every few years, but something that people could read for life.

Outside of comics, it’s a bit harder to say. Joss Whedon’s acknowledged Claremont as a heavy influence, and Buffy feels like the best cinematic translation of what Claremont was doing in comics. More generally, Claremont’s ensemble cast and heavy serialization is the template for basically every prestige TV show of the past fifteen years. Were these show runners inspired by Claremont? Most likely they weren’t, but some were, and his work was a template for character based serialization before anyone else was doing it. Stan Lee definitely pioneered the idea of combining soap opera style ongoing plots and character development with super heroics, but I think Claremont refined and perfected it.

TMS: Tell us a little bit about your upcoming project, She Makes Comics. What is it about, and is it indicative of a trend towards representing women in the comic industry?

PM: I’m producing that project, with Marisa Stotter directing. The film is designed to tell the untold story of women in comics throughout the history of the medium, and also explore the current rise in female fans and creators. I think a lot of people don’t realize that there were women drawing superhero comics in the 50s and 60s, and creating underground comics just as wild as R. Crumb’s in the 70s. In the 80s, a woman in her 20s was the publisher of DC, and was responsible for bringing in the talent who created Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. These are stories that haven’t been told, and we’re going to talk to the people who made history and tell their stories. We’ve shot about 70% of the interviews we want to shoot, and have been working to edit the film together, and I think it’s a pretty compelling story so far.

Just go to Comic Con and you can see that there’s been a huge shift in the demographics of fandom. Emerald City Comic Con just revealed that more attendees were female than male, something no one saw coming ten or fifteen years ago. So, I think women are taking a bigger role in comics, and I also think the medium is less resistant to change than film or TV. Pretty soon, we’ll see this new generation of fans become writers, artists and editors and you’re going to see more change in the medium, and I think that’s cool. Comics should sell more and be read by more people, so broadening the audience is awesome.

TMS: Finally, can we hope to see a future single-subject documentary about a female comics creator?

PM: There’s a couple of people that we’re interested in potentially doing something about, but Marisa’s focused on She Makes Comics, and I’m working now a documentary film about Neil Gaiman. But those will both hopefully finish by the end of the year, and we’ll look into those options then. So, stay tuned.

- Review: X-Men Days of Future Past

- Channing Tatum is Gambit

- Arrow Showrunner To Take Over X-Men Comic After Brian Wood Leaves

Are you following The Mary Sue on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, Pinterest, & Google +?

Have a tip we should know? [email protected]