Spending any amount of time delving into long-running popular monsters will reveal their stories as mirrors and allegories for social anxieties. The modern vampire—as modeled by Bram Stoker’s Dracula—reflects fear about gender, religion/technology, and race, especially in regards to immigration. Godzilla out of a Japan shaken by two atomic bombs and under U.S. occupation after WW2. Zombies are no different.

The creation of zombies is intrinsically tied to the history of Black people and European colonization of the Americas. During the Atlantic Slave Trade, white Europeans trafficked millions of Black people from across West/Central Africa to the Americans. A significant portion passed through the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) until the end of the Haitian Revolution in 1804. In fact, for one of the decades leading up to the liberation of Haiti, one out of every three enslaved persons was held in bondage on the island.

The far reach of enslavement meant these people were only unified (at first) by their status as slaves and skin color. They often spoke different languages and followed different religious practices. To survive and live with one another, a shared culture began to emerge. Influences came from their homes (or the homes of their ancestors if they were born into enslavement), few Indigenous inhabitants, and, via the Europeans, the Catholic Church. The religion that came out of that was Vodou.

Different from Voodoo, Hoodoo, Santería, and Candomblé, enslaved people developed Vodou between the 1500s and 1600s. By finding recurring ideas, Vodou took elements from dozens of cultures altogether to form unique words, practices, and more. Some of these ties came from off the island, while others were born of it. This is where zombies come in.

Vodou and zombies

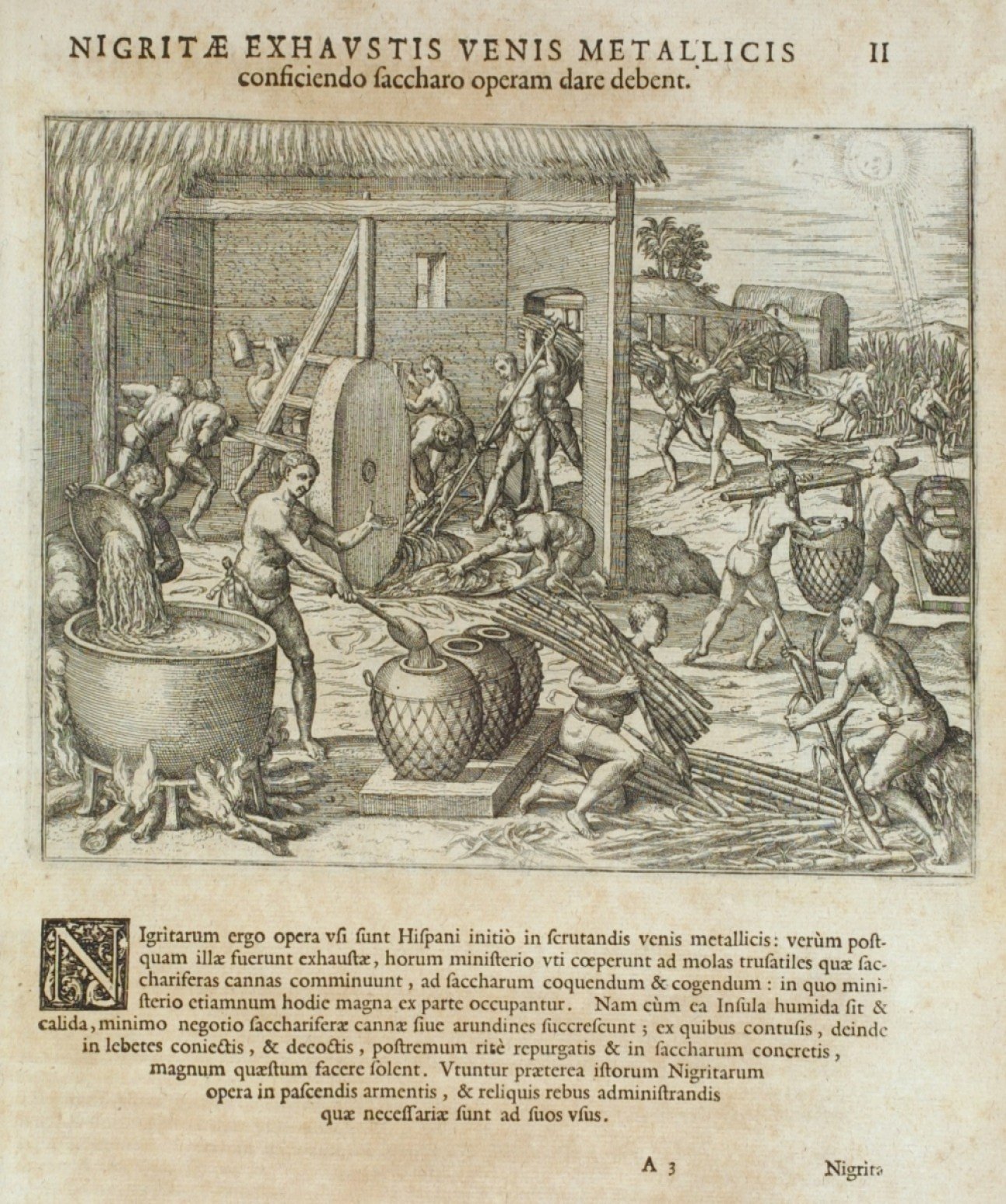

The average lifespan of an enslaved person working on a sugar plantation (a big crop in the Caribbean) was seven years. Most enslaved people didn’t live past 21 on Hispaniola—half the life expectancy of white people in the Americas. Backbreaking and dangerous labor with continual threats of torture and sexual violence made up most of their lives. So, of course, this influenced Vodou. The shared belief that people are made of their physical form and a spiritual one combined with the realities on the ground in Haiti would form the lore around zombies.

Haitian slaves feared that once they passed away (through a zombification ritual), enslavers and bad actors would use their bodies to keep up labor. When “normal” is a life of enslavement, it makes sense that bondage even into death cultivated hellish fear. This continued suffering also serves the enslavers because zombie slaves don’t need what little sleep or food is provided to the living slaves. They could just work non-stop. Zombies are victims and not monsters in Vodou. They do not crave brains or flesh like contemporary versions. In Vodou, zombies act as motorized shells and submit to the master that summoned them.

There’s no universally agreed upon origin or etymology for the word “zombie” or its original Haitian Creole form “zonbi” (“zombi” in French). However various cultures pulled from in the development of Vodou leave clues because there are similar words and meanings. (These are simplified and not exact translations.) The Mitsogho people had “ndzumbi” as a word meaning corpse. Those who spoke Kikongo used “Nzambi” to something with superhuman abilities. Some in West Africa called an object inhabited by a spirit a “zumbi.”

While the current system of labor we have now in the U.S. is terrible, it is nowhere near the horror of slavery. Full stop. Still, we use the words related to enslavement to express the extremes of a feeling or situation. We describe people working mindlessly and separated from themselves as being zombies. We also apply the word to people engrossed in other non-labor activities, like spending several hours on TikTok. Whether the labor is forced or a “choice,” many people fear endless work. That we’ll never get a chance to retire or take it easy. The flexibility of the word “zombie” lives on today.

Zombie exported to the U.S. and beyond

After the U.S. took over Haiti from 1915 to 1935, American marines and journalists brought zombies back with them. However, Americans used the stories to demonize Black people in the U.S. and abroad. The first film appearance of zombies was the Haitian-set movie White Zombie (1932). While the zombies were Black, the main characters were white and the focus of the story. The pre-Code film and the book it was based on (The Magic Island) helped justify the U.S.’s occupation of Haiti. Racists used the film to justify Jim Crow laws and attitudes.

When zombies left Haiti, they became the front-facing monsters rather than the victims. Zombie outbreaks have largely turned into a conduit to tackle other issues. Sometimes these issues still relate to Black history and race, but not always. That doesn’t necessarily need to be the focus but it’s frustrating that most zombie media (with some notable exceptions) is very white. Additionally, Vodou and its aforementioned cousin religions continue to be stigmatized—even in Haiti to an extent—while imagery from these Black religions is culturally appropriated and used to exoticize products. It’s exhausting.

To learn more about this history and pop culture, I recommend watching the 2020 PBS documentary Exhumed: A History of Zombies. It’s on the PBS app for those with Passport. However, you can watch most of it across three videos on PBS Digital Studio’s Monstrum YouTube Channel. Hosted by Dr. Emily Zarka, part one goes into way more detail of what I shared above. It includes interviews with a VooDoo Chief, Horror Noire author Dr. Robein Means Coleman, and Race/Religion expert Dr. Kodi Roberts. Episode two traces the influence of George Romero. The finale delves into the contemporary uses of zombies in media to critique similar issues of the past and modern anxieties—like just how unprepared our governments are for a global pandemic.

(featured image: Cottonbro studio via Pexels)

Published: Nov 1, 2023 10:10 PM UTC